Children’s Dreams of Future UK Treescapes Envisioned through Games

October 2023 - November 2024Funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Future of UK Treescapes

Undertaken as X||dinary Stories with Eleanor Dare

PI: Simon Carr (University of Cumbria).with partners at MMU, Middlesex University and the Mersey Forest

This project seeks to engage children in the development of videogames about treescapes to encourage young people more widely to engage critically with trees in their local environment; not just rural but also urban trees.

The research team is led by Simon Carr at the University of Cumbria and includes partners at MMU and Middlesex University, The Mersey Forest with myself and Eleanor Dare working on the project as independent games designers from X||dinary Stories.

Together we have been working with children from two schools (one primary and one secondary) within The Mersey Forest area to bring children aged 8 to 13-years-old into the design of an online game where children can learn about some of the key principles about tree care and planting valued by the Mersey Forest.

Aims

Through a series of practical workshops with school children myself and Eleanor co-created characters, a gaming narrative and environment that we are now including in a Roblox Game.

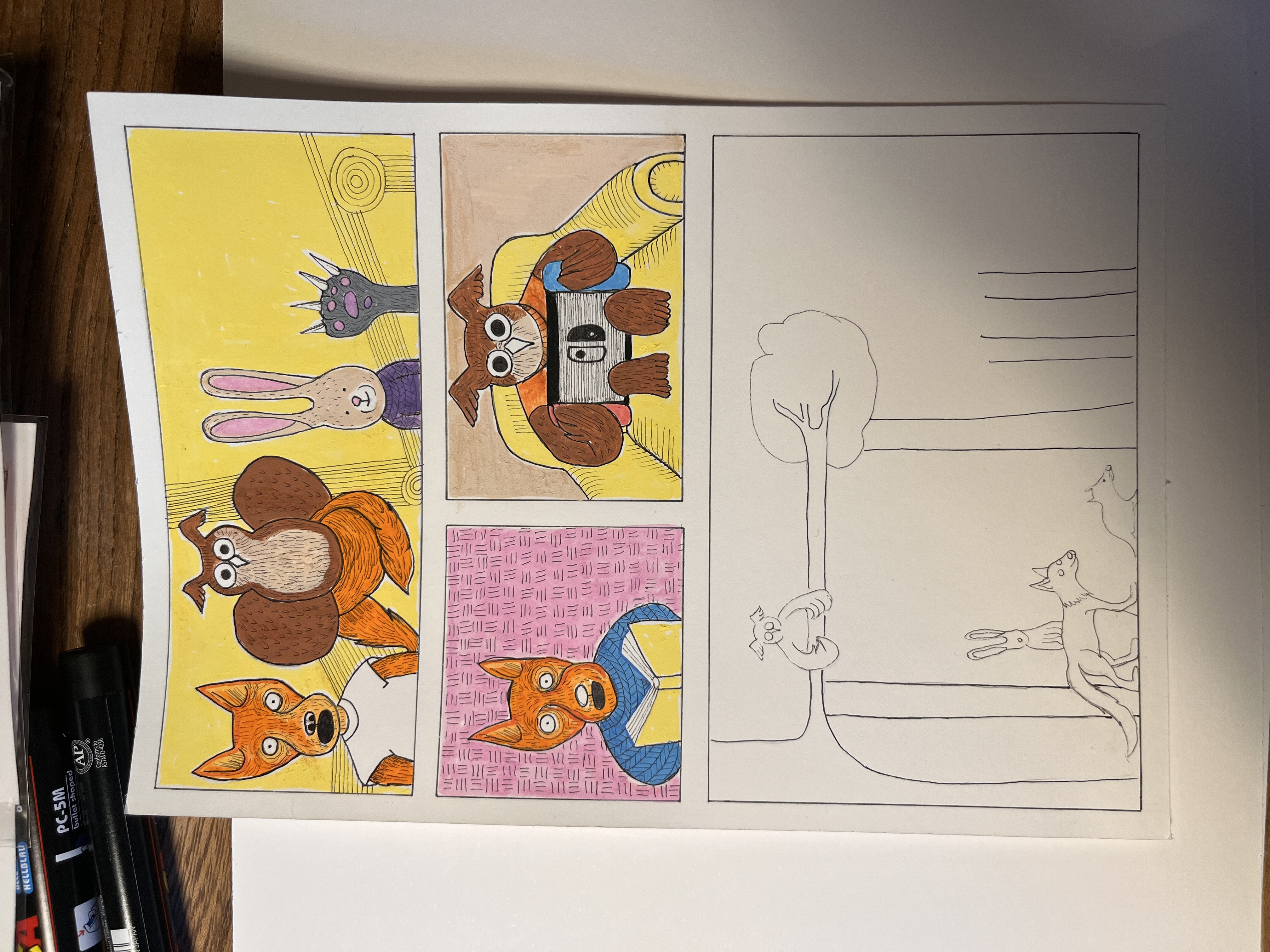

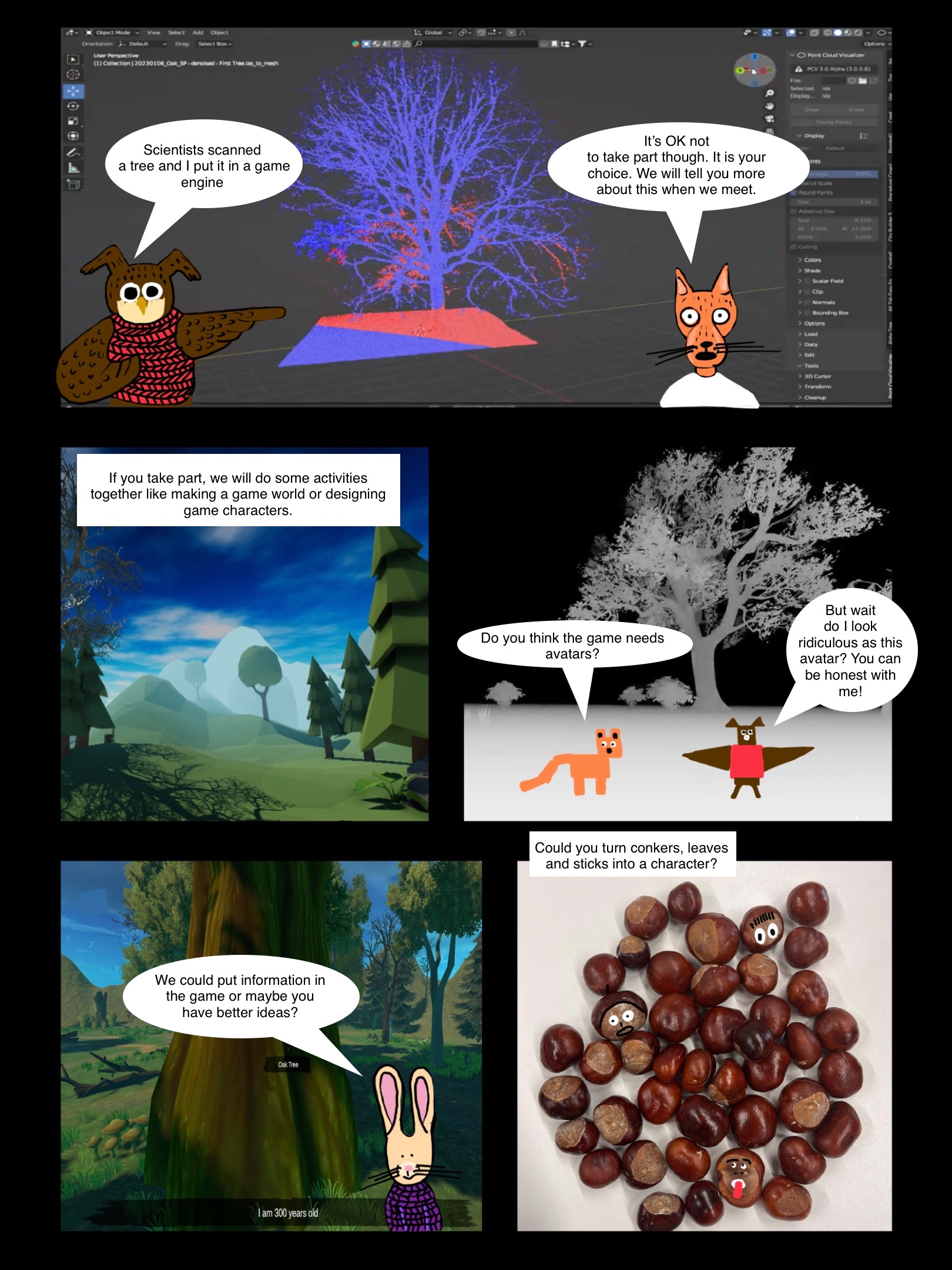

As part of the University ethics application process, I produced an information sheet in comic form to let potential participants know about the project and what would be expected of them should they wish to take part:

Participant Engagement Workshops

The workshops took place with primary and secondary school children and wer broken down to focus on different core elements used in game design: (1) Game Worlds, (2) Character Design, Narratives & Gaming Mechanics.

Game Worlds

Children were asked to make a ‘paper’ prototype gaming world based on the notion of a future urban treescape/ forest or woodland:

I always test the ideas before beginning the workshops with children to see how materials respond, how easy it is to do, and time the length of the activity:

I began by using natural materials to challenge common gaming aesthetics but threw in a Minecraft Lego mini figure to reference the videogames kids love.

The extent to which children enjoy gaming can be evidenced just by considering one standalone statistic that 147 million children play the online game Roblox each week. As Roblox is a free-to-play gaming platform accessible via computer, tablet or phone, we are currently considering it for our game. The sheer number of Roblox users makes it more likely that it will be used by other children than if we were to launch a game on another platform and there is also no paywall.

The sister platform, Roblox Studio provides a free game development space. Whilst readymade digital assets and base plates offer fairly low-poly gaming aesthetics, it is also possible to develop more sophisticated models in other industry standard software that can later be added to Roblox Studio and programmed. Adults are increasingly using such methods to create games for children that are essentially online adverts aimed at driving real-world sales. I was surprised to hear at the Children’s Media Conference a couple of years ago that only 10 percent of children have ever used Roblox Studio themselves.

As a result, I am interested in creating spaces where children can question gaming aesthetics that are made for them, and as part of this encouraging them to create alternatives. In my work to date, I have found that children, even those young in age are strong critics of digital games and content, yet the chance to understand that gaming aesthetics are also a decision made by adults and not a result of the technology is something lesser expressed. For this reason, and also because this project is related to treescapes, Eleanor Dare and I planned the first workshop so that children could design gaming worlds from natural materials.

This also seems to relate to one of the Mersey Forest’s aims which is to get children to engage with trees in real world contexts. One way in which adults tend to go about trying to use games for educational purposes is to replicate worlds or knowledge literally. Yet, children rarely do this in their own play (especially younger children). Instead, they merge fact and fiction more readily. As a result, I began thinking about how the handling of natural materials could provide more subtle ways to link digital and real treescapes. Furthermore, should they be interested it could even be possible to use aesthetics of natural materials in the game we develop.

In the workshop children were asked to work individually or in pairs/small groups to make a physical model of a game world based on treescapes. They were told that treescapes could mean a forest or a wood, but it could also be those in an urban environment or a singular tree.

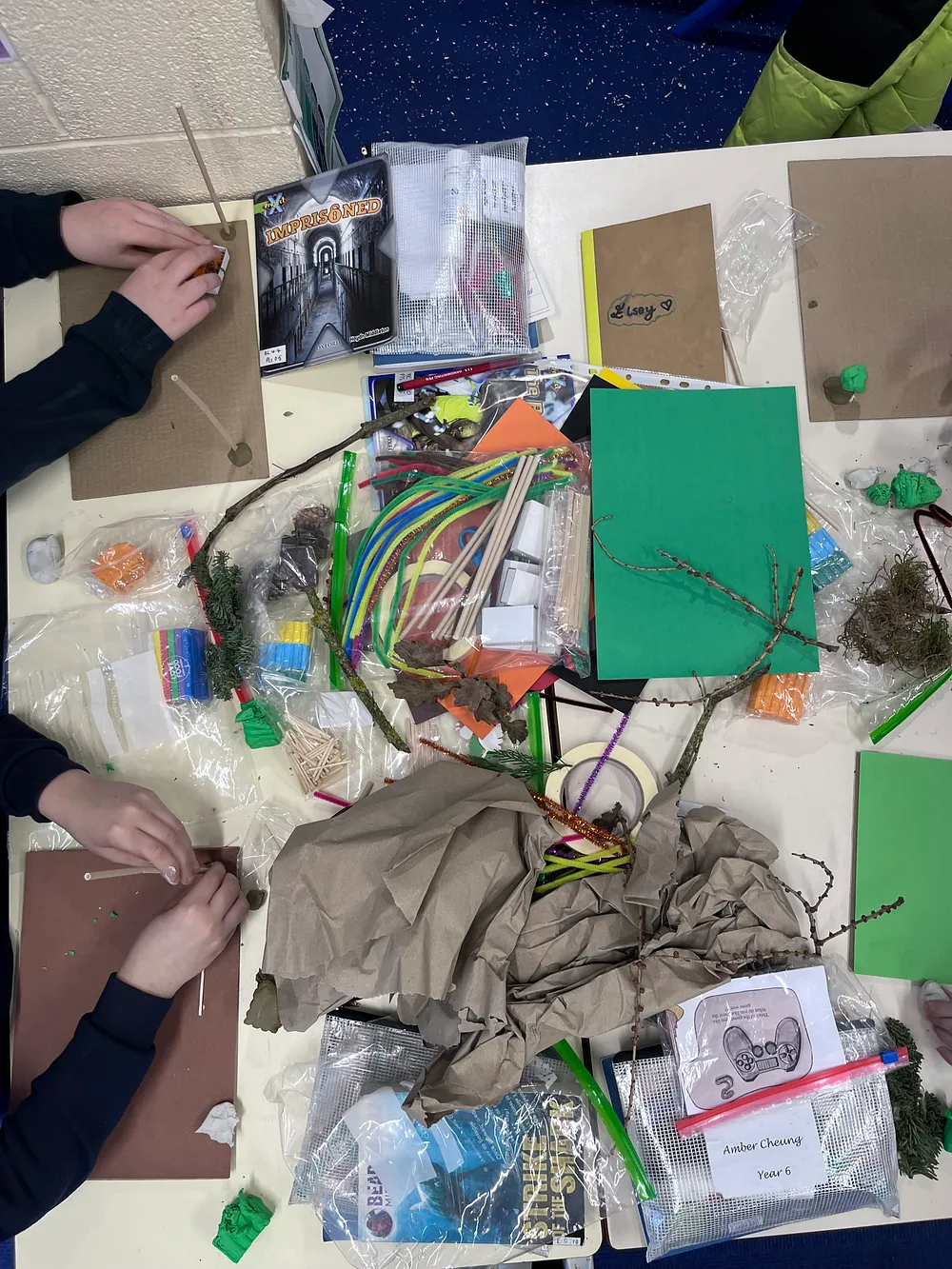

To produce the game world models we used a “Cultural Probe” approach (see e.g. Gaver et al, 1999; Wargo & Alvarado, 2020) where physical materials were offered as design prompts. To this end, children were given packs of craft materials containing, coloured paper, pipe cleaners, google eyes, coloured plasticine and modelling clay. As well as, a range of natural materials, twigs, pine cones of various sizes, conkers and sticks or bits of lichen etc.

In offering children such a wide range of materials, I was also drawing on ideas from Pauliina Ratios’ (2013) work about how materials have agency that draw children differently to them. Finally, children were provided with a Minecraft LEGO Minifigure. This was given to provide a context for scale in building their worlds, but also it was intended as a reminder that we were doing this as part of digital game design and development; Minecraft being a game most children are familiar with.

It feels worth noting that the natural materials brought moment of chaos into the classroom when unintentionally insects emerged from them. This reminded me of the importance of more-than-human theories as well as how young children often include animals in their play because they deliberately allow for chaotic storylines to emerge because they can not be expected to be confined to human rules, which is why when you watch young children playing “house” nearly always one child is assigned the role of a dog.

After children had made their game world models they were shown how to use photogrammetry to scan and turn them into digital assets, thereby demonstrating the move from physical materials to digital.

Junior and Secondary School Students Scanning their Models using Photogrammetry

As a result, I tend to explore common ideas and features alongside “outliers”. For example in the world building workshops, there were lots of treescapes that contained narratives about the variety of trees, an interest in the age of trees such as by placing value on old trees by giving them special powers within their game designs. Of course, animals appear and many children created homes for them, e.g. hives or caves. Yet, on the fantastical level one group also produced a dystopian forest in which people believe they are going to relax, but in actual fact are under government surveillance. This was indicated by placing “googly eyes” on animal figurines, hidden in vegetation and on bark on the ground.

Image: Dystopian Government Surveillance Forest

Image: Dystopian Government Surveillance ForestAs a game designer my interest is in both these view points: the everyday common narratives as well as fictional ones, and both will be kept in mind as we see where the second series of workshops on character design take the project.

Characters, Gaming Narratives & Mechanics

As part of the preparation for thinking about gaming narratives, I began by looking at a range of narratives in children’s books about trees. It is useful to think about if there were game versions of these stories what bits would be kept, where would interaction come in etc.

Kress (2010) writes about how different modes of communication make it possible to gain or lose the ability to express information. For example, what can be conveyed in sound is not the same as in image, nor is it identical to what can be disseminated in writing. This is because English writing is a linear process that moves from left to right and is based on symbols that represent phonetics. Whereas gaming narratives are non-linear because they predominately utilise affordances of the visual mode that uses spatial conventions. Further, gaming narratives are often embodied by the player and are interactive meaning movement is also a core convention. Thus, when designing a methodology to work with children in game design it is important to utilise the modes of communication most in tune with this so they can think through the related materials and be able to fully articulate their ideas.

Drawing on communication theory, such as briefly mentioned above, in the past I have asked Masters students working on videogame designs to embody their character ideas before making them digitally. Even extending to ask postgraduate students to consider “living” as their character for 24-hours to see how they would embody everyday scenarios so that they can add additional depth and ideas to how their character designs might respond in the digital world they create later.

Image: Living as a game character (Yamada-Rice, 2020)

Image: Living as a game character (Yamada-Rice, 2020)The children’s TV show writer and creator, Andrew Davenport, also provided a strong influence on the development of my ideas in this area. While working with him on his show ‘Moon and Me’, I mentioned that it was rare that so much research and time went into the development of fictional TV characters for very young children. He responded with a poignant story about a child who had been neglected and died alone holding a toy version of one of the characters he had made. Character design for children, he told me, should be of upmost importance because you never know how that character is going to come into a child’s life or how significant the relationship they have with your character might be. It is a devastating story but an important reminder that we must design well with and for children.

In addition, there are artists who have also inspired my interest in embodying characters such as the beautiful work of Charles Freger and mask designers, Damselfrau.

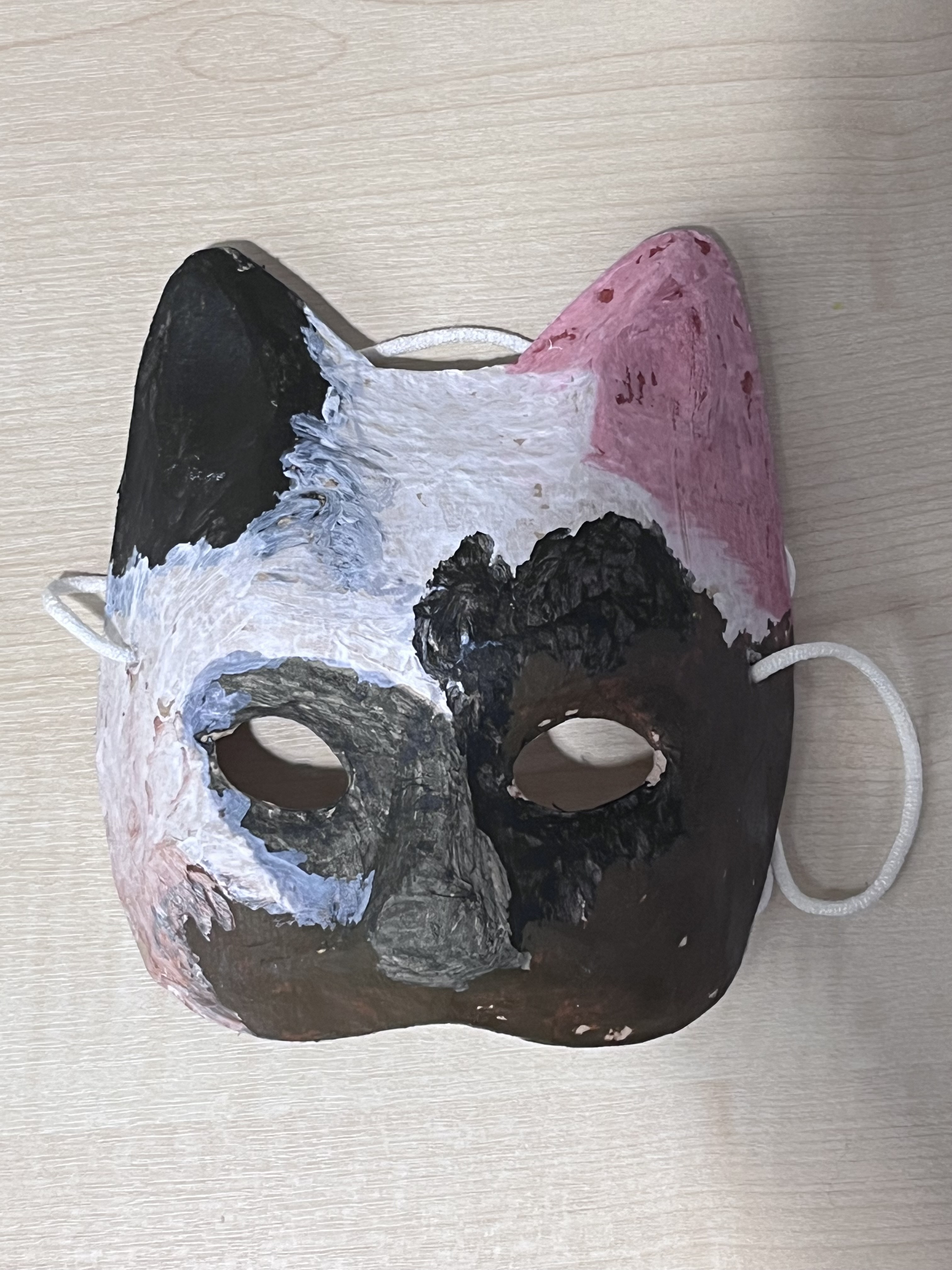

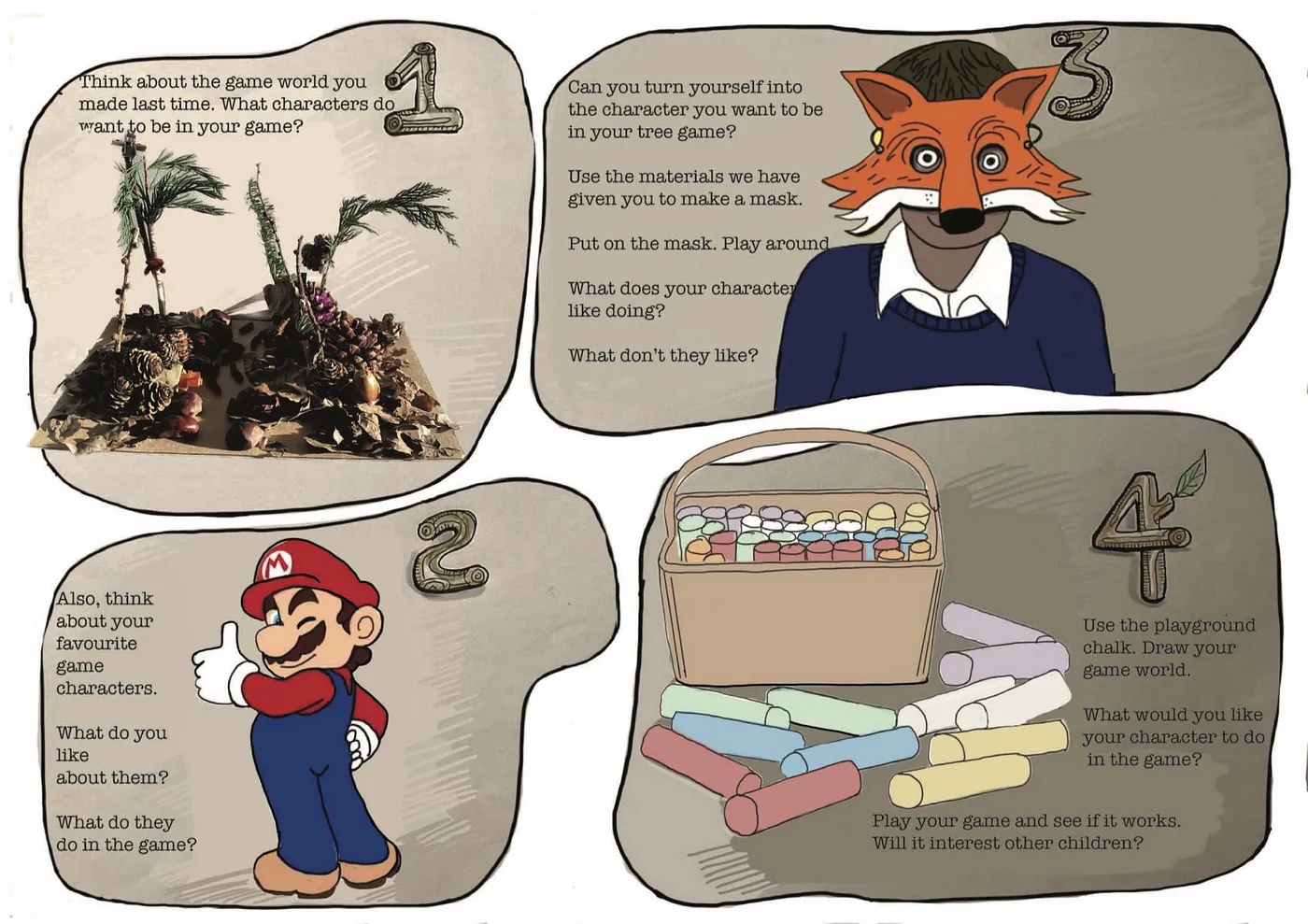

I thought this idea could be used with the children in our project on a smaller scale. As a result, we decided to set children the prompt of making a mask and embodying their character in the school playground.

Image: Design prompt for the character design and gaming mechanics workshops (Yamada-Rice, 2024)

Image: Design prompt for the character design and gaming mechanics workshops (Yamada-Rice, 2024)As time with the children was limited, we took a selection of base masks for them to use as a starting point. As with the previous workshop, children were also presented with a wide range of craft and natural materials to work with. This drew on the idea that:

“Thinking with and through materials, their signification, their origins and life cycles, can animate one’s relationship to the living and non-living world. As a little push back against alienation it can also enliven one’s sense of responsibility towards that world.”

(Dittel & Edwards, 2022, p.5)

Thus, by providing a selection of natural materials with other selected elements like stickers of eyes from anime and manga, we hoped to provide material links to children’s interest in popular culture which is often connected to gaming and at the same time provide direct links between that and trees and the natural environment.

Watching and talking to children as they made masks, I was aware that it felt chaotic compared to their regular school classes. Having done a PhD and MA in Childhood Education I am often critical of formal UK schooling and its lack of opportunities for children to engage with the arts, music and making as forms of knowledge enquiry and making equally as important as STEM subjects.

I feel depressed when I think that UK school children are forced to rote learn much of their education, not even having free access to basic human rights such as going to toilet when they want.

I began thinking about the correlation between educational oppression and the climate crisis. For Crary (202), like others, there is a direct relationship between neoliberal structures that include constant extraction from the Earth and the climate crisis. Formal educational curricula are of course intrinsically neoliberal, and hence it could be argued are also entangled with the climate crisis.

Crary is radical in his approach and writes that climate recovery cannot come about until the end of capitalism, much of which he writes is driven by the advancement of technologies and digital forms of communication, and that to maintain natural ecology we must move to embrace more hybrid analogue and digital ways of living:

“If we’re fortunate, a short-lived digital age will have been overtaken by a hybrid material culture based on both old and new ways of living and subsisting cooperatively. Now, amid intensifying social and environmental breakdown, there is a growing realization that daily life overshadowed on every level by the internet complex has crossed a threshold of irreparability and toxicity.”

(Crary, 2022, p.1)

This also acts to reinforce the importance of designing videogames with hybrid digital and analogue materials some of which directly derive from treescapes.

The project team includes a philosopher, Johan Siebers (Middlesex University), who brings various lenses to the project, one of which is the notion of hope. We chatted in the evening before these set of workshops began about schools and their philosophical connection to prisons. Then on the way home, I took his advice and read Freire’s (1967) ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’ which fuelled my thoughts on the connection between educational oppression and the climate crisis further.

Freire writes of formal education being used to oppress and I believe many of his ideas have stood the test of time. Perhaps one key point of divergence is that Freire writing in the 60’s states that students were not aware that pedagogy was oppressing them. Whereas I think children are strongly aware that schools are oppressing them (especially since school closures during COVID). Indeed, several children asked me directly why they don’t usually get to have classes like the workshop I was delivering, or not to leave as they did not want to return to lessons, or even to get them out of the school. A literal cry for help!

Simultaneously we also know that children are much more likely than adults (of my generation and above) to suffer from climate anxiety. Yet the UK National Curricula across primary and secondary education has a patchy, possibly neglectful approach to teaching issues connected to the climate crisis. This was evidenced in the “State of the Nation” research conducted by Dubit and the Children’s Media Foundation.

As a result, designing a videogame about treescapes while working with natural scientists and the Mersey Forest, as well as, educationalists and schools suggests that we cannot ignore the messy politics that lie behind both formal education and the climate crisis and their entanglement with one another and thus the need to urgently care for trees.

Despite my pessimism, both Johan and the Mersey Forest regularly bring ideas of hope to the project. For example, Su and Dave from the Mersey Forest talked about planting trees without really knowing how future generations would use them- hopeful spaces. Then, in the evening between the workshops in schools many of the project team went to a bowling, Karaoke and gaming complex, which Johan pointed out was called Free-dom. The kingdom of freedom was an arcade for playing- how apt! Could it be said that hope comes from things that cannot be measured or completely accounted for (freedom)? If so, perhaps the best direction for our videogame is to create a sandbox space for free play?

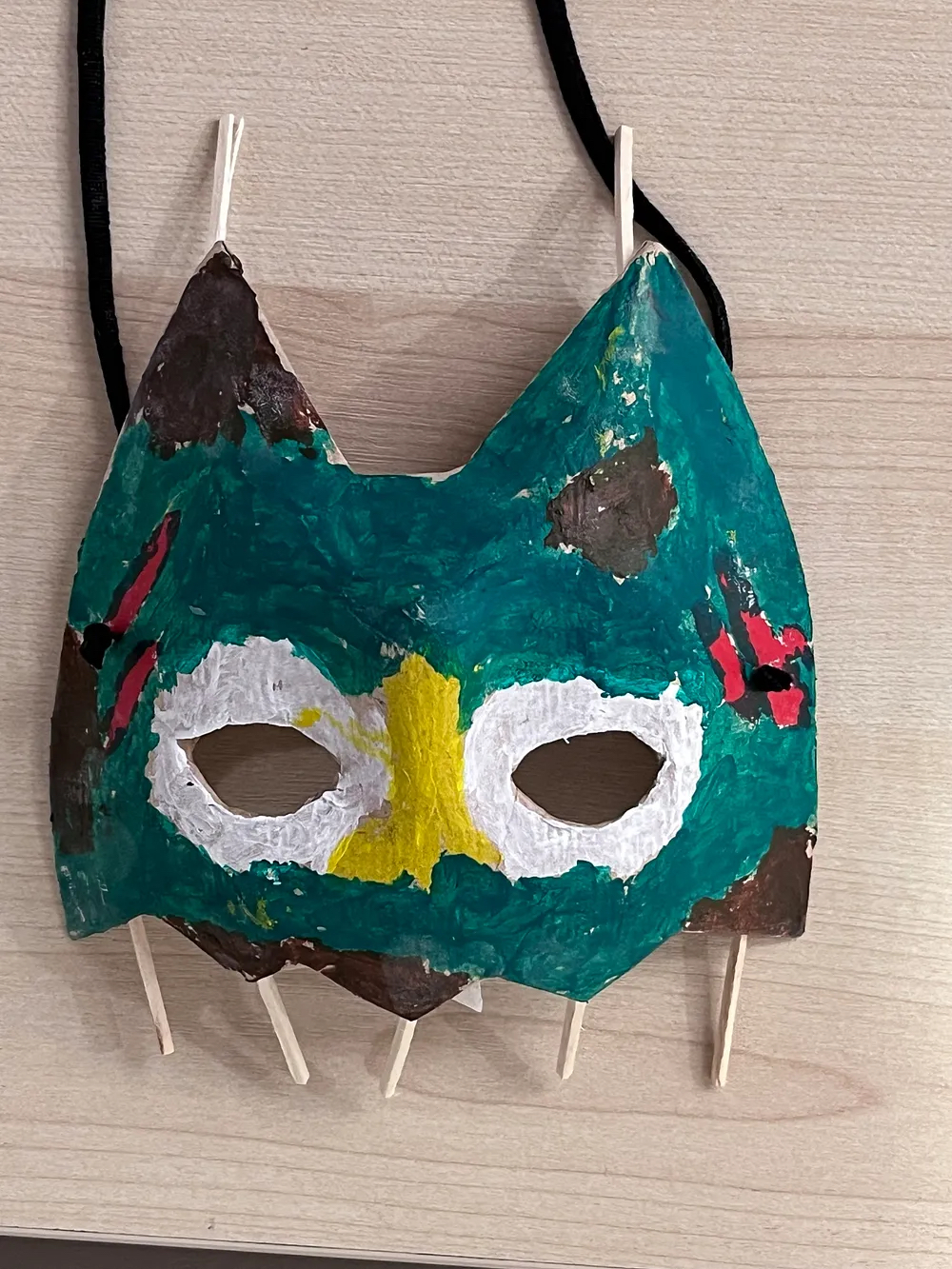

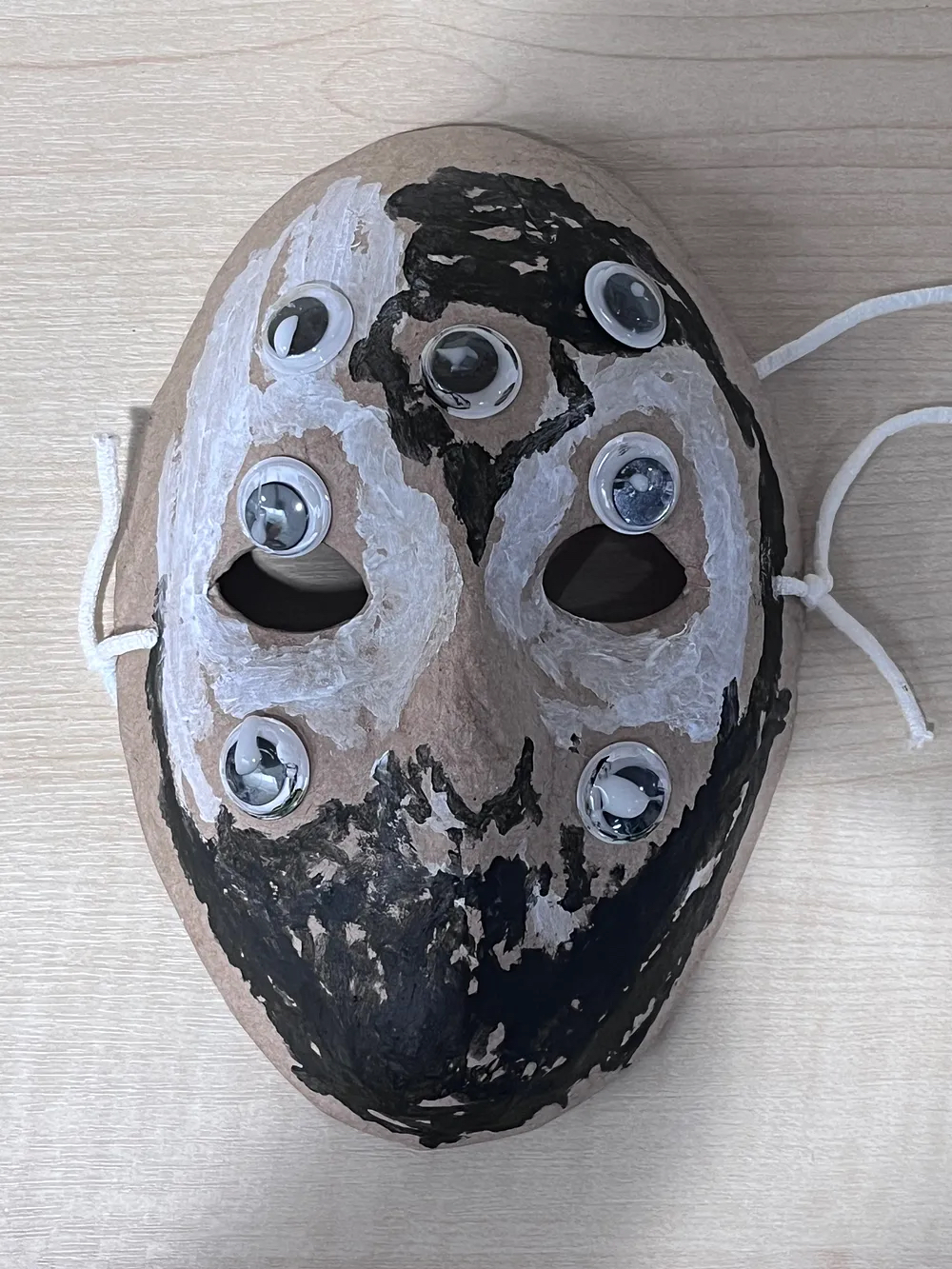

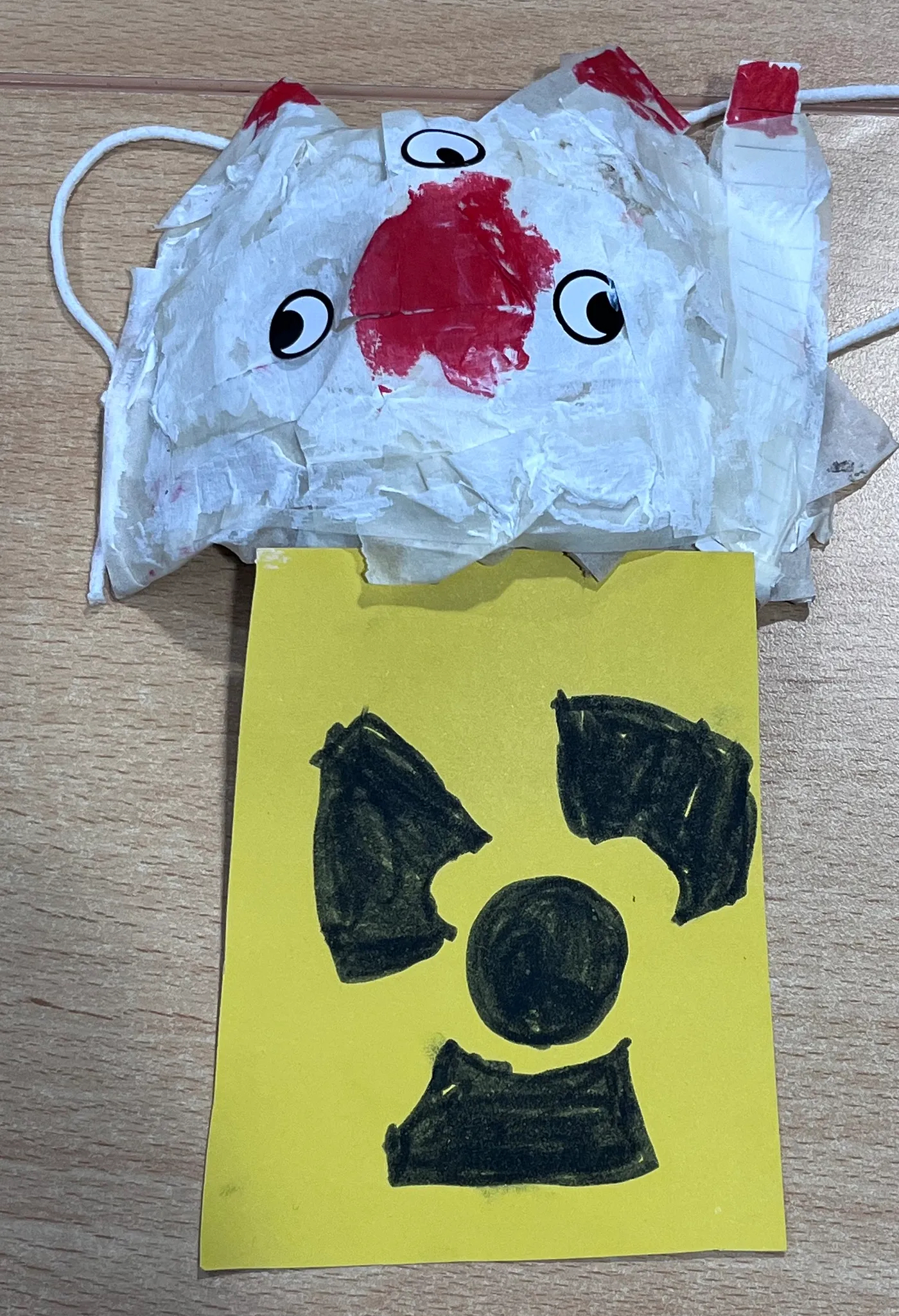

Children, but especially primary school aged children produced an enormous variety of detailed masks. Some of which are shown below:

Character design masks made by primary-school children

On the way to a work event in London, I began analysing some of the data from the character design workshop that included the masks above, but also video recordings, and field notes. Although I have still only scrapped the surface of analysing these, it seemed there was a thread emerging that the children hoped the gaming narrative would portray non-human life powerfully rising up against us. If humans can’t curb themselves to maintain the planet then the rest of life will curb us. (Their) Hope.

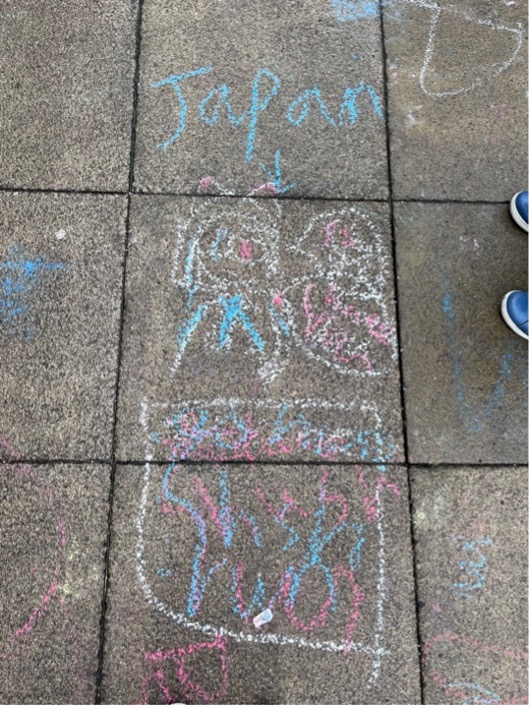

For example, one child made the following mask:

Intrigued by the radioactive symbol she had drawn and attached to the mask, I asked her what she had made. She asked if I knew what the symbol meant and I said I did, did she? She said it referred to wastewater the Japanese government had recently decided to release into the ocean after the collapse of part of the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant following the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, which she believed is still radioactive. The water, she said will create radioactive super animals, like the cat she had made to rise up and fight these humans who are putting the wastewater in the ocean. Whether you agree with this child or not, it is a very powerful political statement for a primary school aged child to make.

These powerful narratives of nature conquering human life reminded me of the small moments of disruption that the insects which escaped from the natural materials in the last set of workshops (as written about in a previous blog post) brought to the classroom.

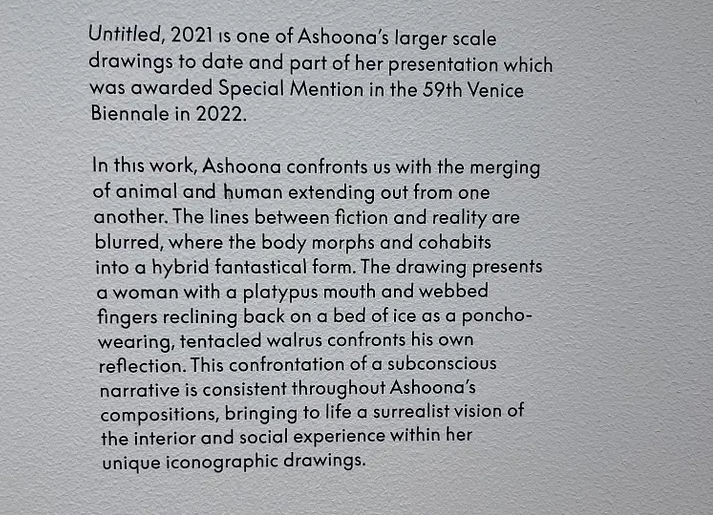

By chance the same day as I began analysing the materials from the character design workshops, I went to see Shuvinai Ashoona’s exhibition“When I draw”. I was faced with the beautiful collection of drawings while the children’s ideas were still in my head. The Inuk artist in living so closely to other forms of life draws human-animal/fish form combinations. It’s a simplistic thing to take from the work but it moved me to think abouthow her close connection to nature removed the distinction often made between humans and other life forms.

Finally, videogames are so important to children that many of those that took part in the workshops could not slow their speech down enough so that I could grasp all they wanted me to know about their ideas. Yet, somehow this show helped further my thoughts about the children’s expressions of treescapes, that included real and mythical animals, as well as hybrid human-animals just like in Ashoona’s amazing drawings.

More than ever, I think it will be the wrong path to make an educational videogame that presents a literal representation of treescapes or simply tell children to plant trees. Children’s ideas are messier and more complex than this, but so are the politics behind the climate crisis and indeed their formal education structures as I have tried to begin articulating here. I think we should trust children to be capable of making connections to the wider topic about the importance of future treescapes even if we do not say this explicitly within the videogame.

References

-Crary, J. (2022) Scorched earth. Beyond the Digital Age to a Post-Capialist world. London/New York: Verso

-Dittel, K. & Edwards, C. (eds) (2022)Material beyond extraction and kinship beyond the nuclear family. Onomatopee 208.

-Freire, P. (1967/2017) Pedagogy of the Oppressed.Penguin Modern Classics.

-Gaver et al (1999) Cultural Probes. Interactions

-Kress, G. (2010) Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. Routledge.

References

-Rautio, P. (2013) Children who carry stones in their pockets: on autotelic material practices in everyday life. Children’s Geographies, Vol. 11(4), p.394–408.

-Wargo, J. M. & Alvarado, J. (2020) Making as Worlding: Young children composing change through speculative design. Literacy, Vol. 54, p. 13–21.

Trees Videogame

Right before Eleanor Dare began work on the development of the videogames one of the issues we discussed was how to deal with two seemingly disparate desires for the game that arose from the children’s ideas, and those of the major adult stakeholders. For example, the Mersey Forest and the tree scientists had an educational agenda and values they wanted to pass on to children about how to interact with and care for trees, as well as very specific lessons they wanted to share about tree types and their growth. On the other hand, the children’s ideas were more fantastical having created mythical creatures and magical trees with golden acorns, and special powers as they aged. Yet, as I discussed previously, these child-designed narratives were rarely superficial but rather created to illustrate their awareness of politics and concerns about and ideas connected to the climate crisis.

I began thinking about ideas from when I had previously studied Japanese History and Japanese Art History. Specifically how Edo, the predecessor to Tokyo, had been controlled to such an extent that it necessitated the development of the Floating World (1615–1868). The two spaces lived in symbiosis with the Floating World acting as an escape for play and pleasure from the mundane and regimented life of Edo city. To me this reflects the differences between formal education and learning through free-play, as well as, the everyday structured school learning of the children we worked with, compared to the more chaotic workshops where children expressed their ideas and knowledge about trees through a range of analogue and digital making that was only loosely controlled.

In the same way, we thought that the videogame could have an urban landscape with more direct references to tree types, their growth and how they should be looked after, in short more controlled like Edo or formal schooling.

Thus, conversely the outskirts of the town could be a mythical treescape based on the children’s ideas, which would be freer and allow possibilities for free-play and learning and exploration that occurs in such spaces too.

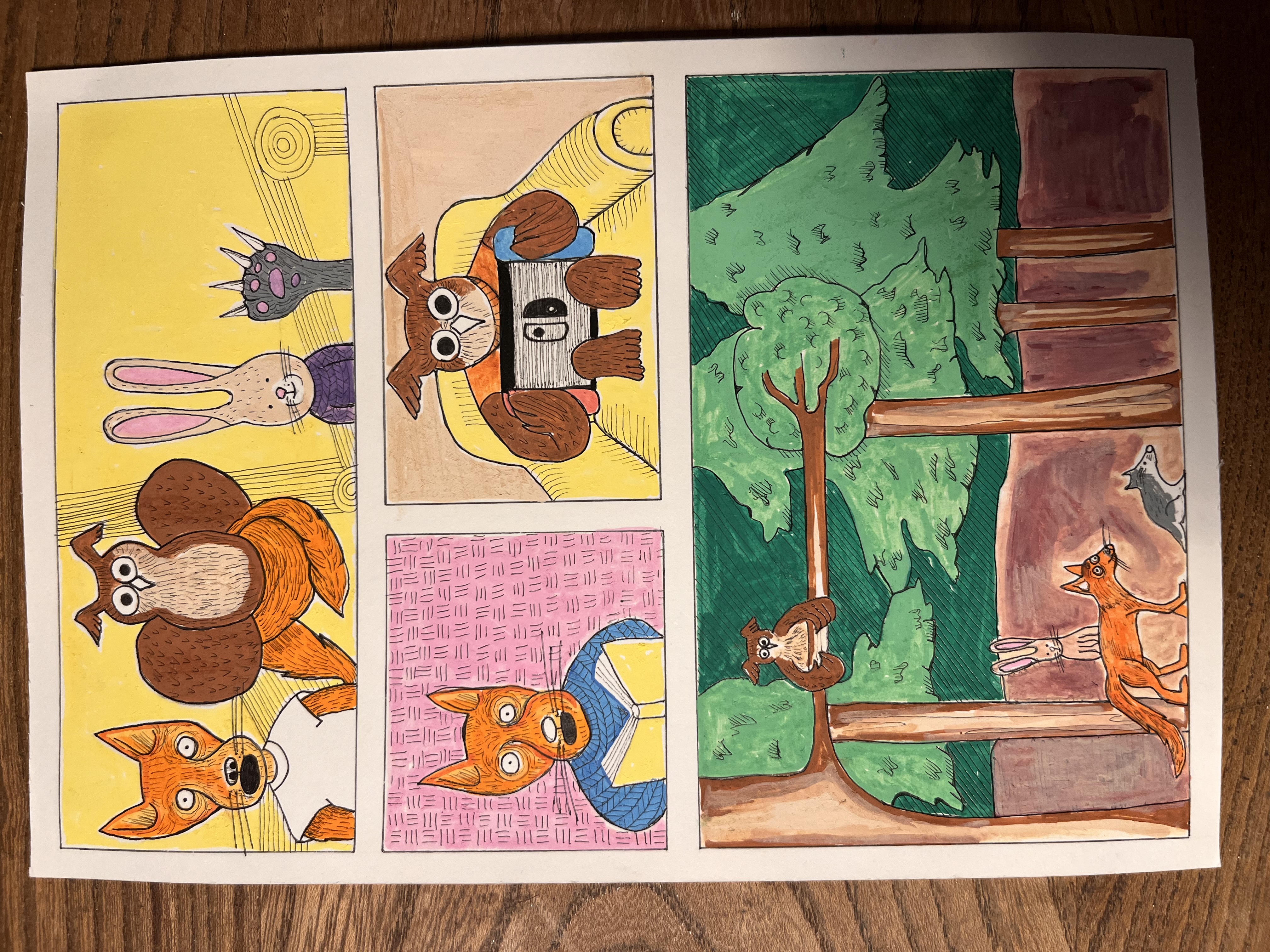

Simultaneously an MA Experience Design student, Brandon Barnard that I was teaching at the time, began working with some of the ideas from the school workshops as part of my inclusion of the Trees Project as a “live project” in one of the modules he opted to study. In exploring the masks and narratives the children had created, Brandon came up with the idea of turning them into comics that would then be hidden amongst trees in the videogame. He used paper prototyping to test the idea in the real world.

Brandon was not aware of the discussions Eleanor and I had been having about Edo and the Floating World, so unbeknown to him I could also see parallels between his comic idea and Edo period art. In the Tokugawa period stories of the Floating World were brought back to Edo through woodblock prints that became known as Ukiyo-e. It has been suggested that the production of Ukiyo-e became the first time in Japanese history that art was produced for the masses. This is also similar to the history of comics.

Thus, I began to see how I could extend Brandon’s idea to turn children’s character and narrative designs into short comics that could be digitally geocached in the game, providing tales of the mythical and playful treescape outside the city boundary.

More of the comics and the children’s ideas that were used to develop them, can be found here.

The collaborative ways of working that Eleanor and I use as a mainstay to our collaborative and individual practice-based research usually brings together threads from disperse areas to create new meanings and possibilities. This time it has brought me joy that a small part of the trees videogame is also a very subtle ode to Edo, the Floating World and Ukiyo-e.

Publications

The project was showcased RMIT’s Critical Forest Lab

Photo Gallery